Jimmy Atterholt

Near a granite dome in the Sierras

Research Blog

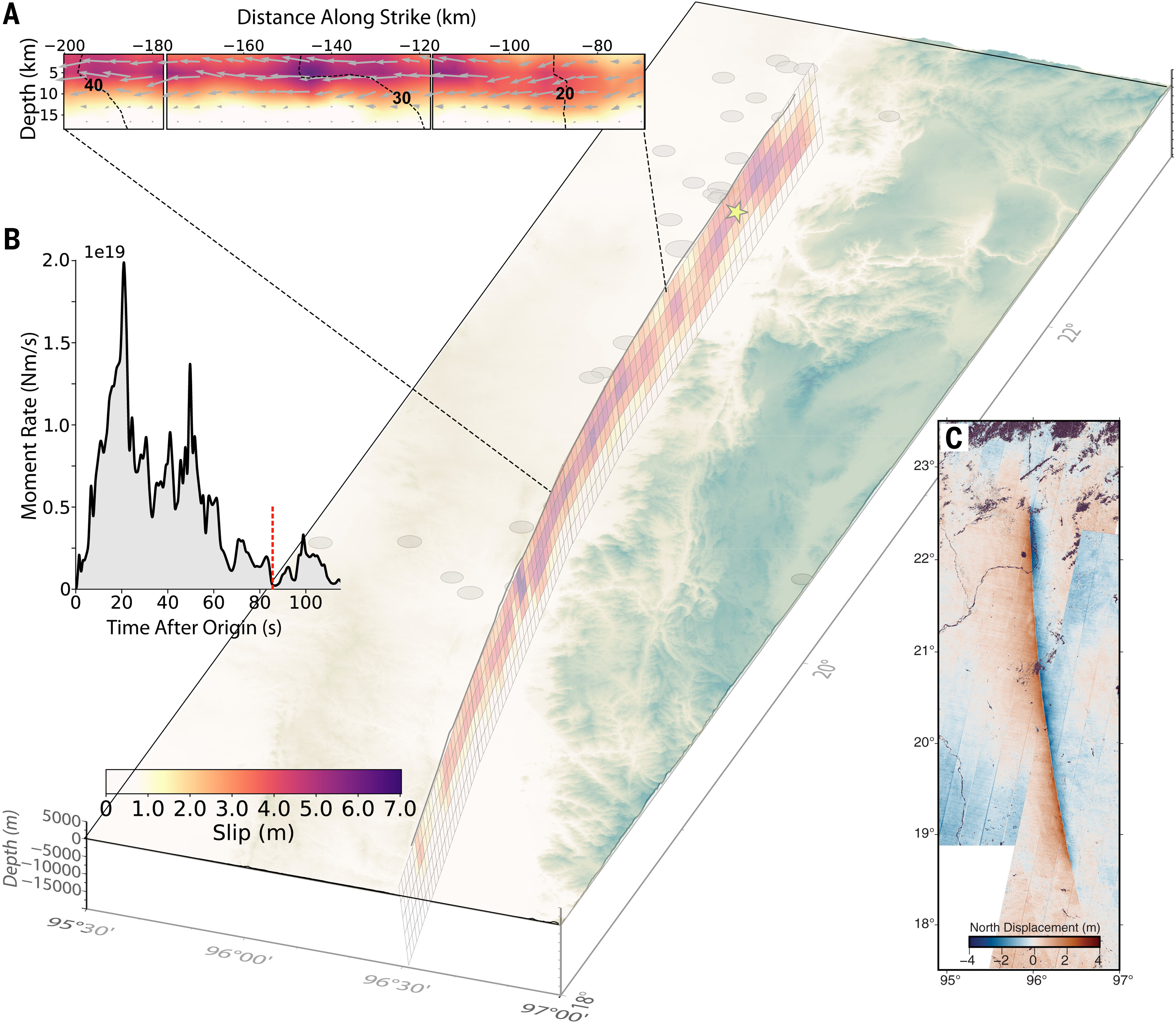

Mandalay Earthquake Imaging (October 2025)

Following the devastating Mandalay earthquake earlier this year, my colleagues and I at the Geologic Hazards Science Center used a range of techniques to image the rupture in detail. Led by Dara Goldberg and Will Yeck, our study shows that the earthquake was unusually long for its magnitude and ruptured at surprisingly high speeds, with a large portion of the fault slipping at supershear velocities. This event may be an analog for large ruptures on the San Andreas Fault, and our results challenge some of the assumptions commonly used to estimate hazard for major strike-slip earthquakes. Read more in our paper in Science here.

|

|---|

| Mandalay Earthquake slip distribution. |

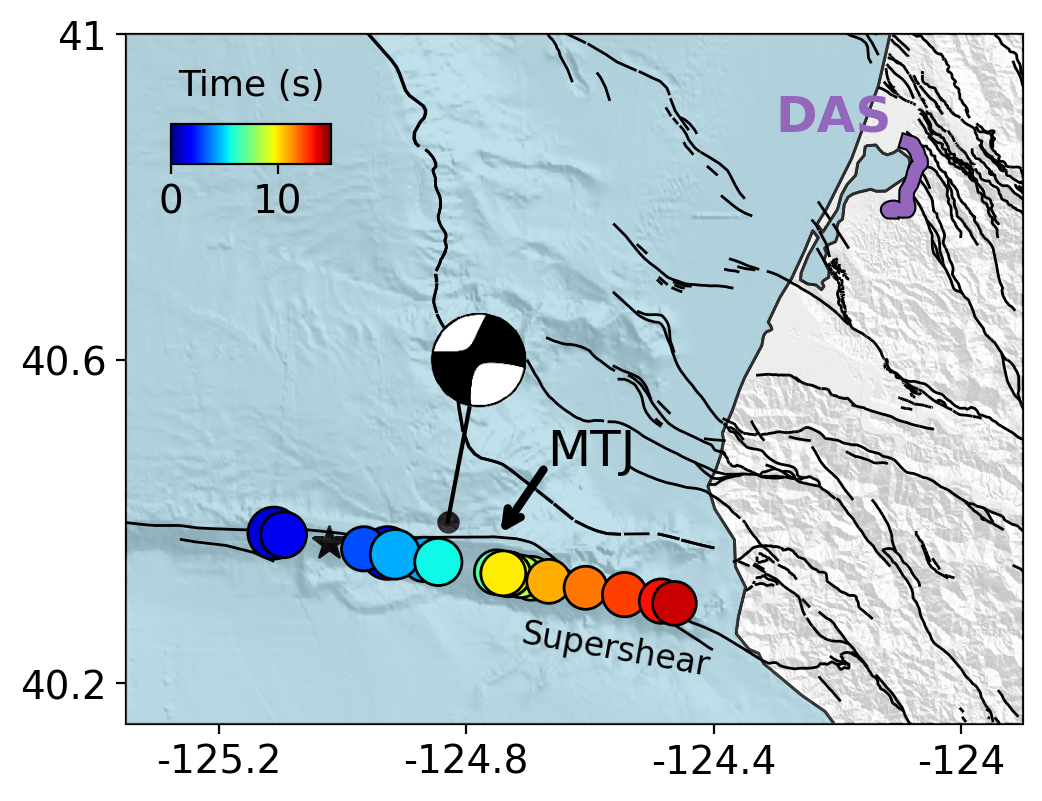

Imaging a Big California EQ with a Fiber (September 2025)

In December 2024, a magnitude 7 earthquake ruptured off the coast of Cape Mendocino—the largest California earthquake in five years. Because it occurred offshore and outside the regional seismic network, the rupture was difficult to image with standard techniques. But it was captured by a nearby distributed fiber-optic array. Using array seismology on this fiber dataset, we were able to image the rupture propagation at high resolution and made two key observations. 1. Supershear transition: our fine-scale rupture image clearly shows the earthquake accelerating to supershear velocity, shedding light on why some ruptures go supershear. 2. Rapid rupture characterization: by analyzing just the first several seconds of the P-wave, our method resolves rupture directivity and length, pointing to how compact fiber arrays could improve earthquake early warning alerts. Read more in our paper in Science here.

|

|---|

| Rupture image produced in this study. |

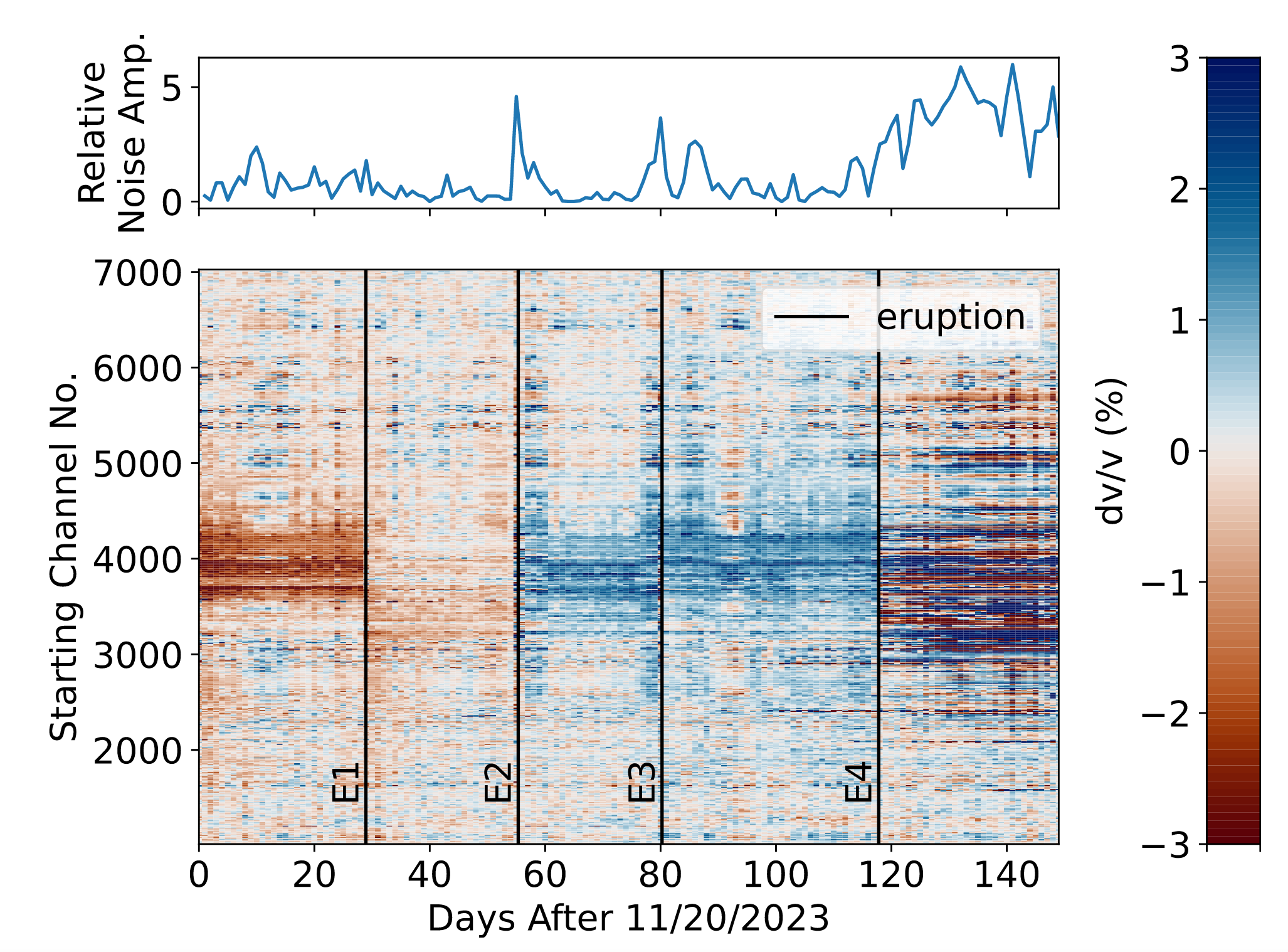

Tracking Dike Opening with Fiber in Iceland (February 2025)

When magma moves through the earth it deforms the rocks around it. This deformation can change seismic velocities in measurable ways. In 2023, an eruption started in the Reykjanes Peninsula in Iceland. A team at Caltech deployed a fiber-optic sensing array using a 100 km-long fiber and captured this eruption sequence. Led by Eli Bird, we measured changes in seismic velocity across several eruptions. From these measurements, we can infer the location, length, and depth of the dike responsible for the eruption using a Bayesian inversion. This is a new and exciting way to monitor ongoing volcanic events using existing telecom infrastructure. Check out the paper in AGU Advances here.

|

|---|

| Velocity changes across eruptions shown in this study. |

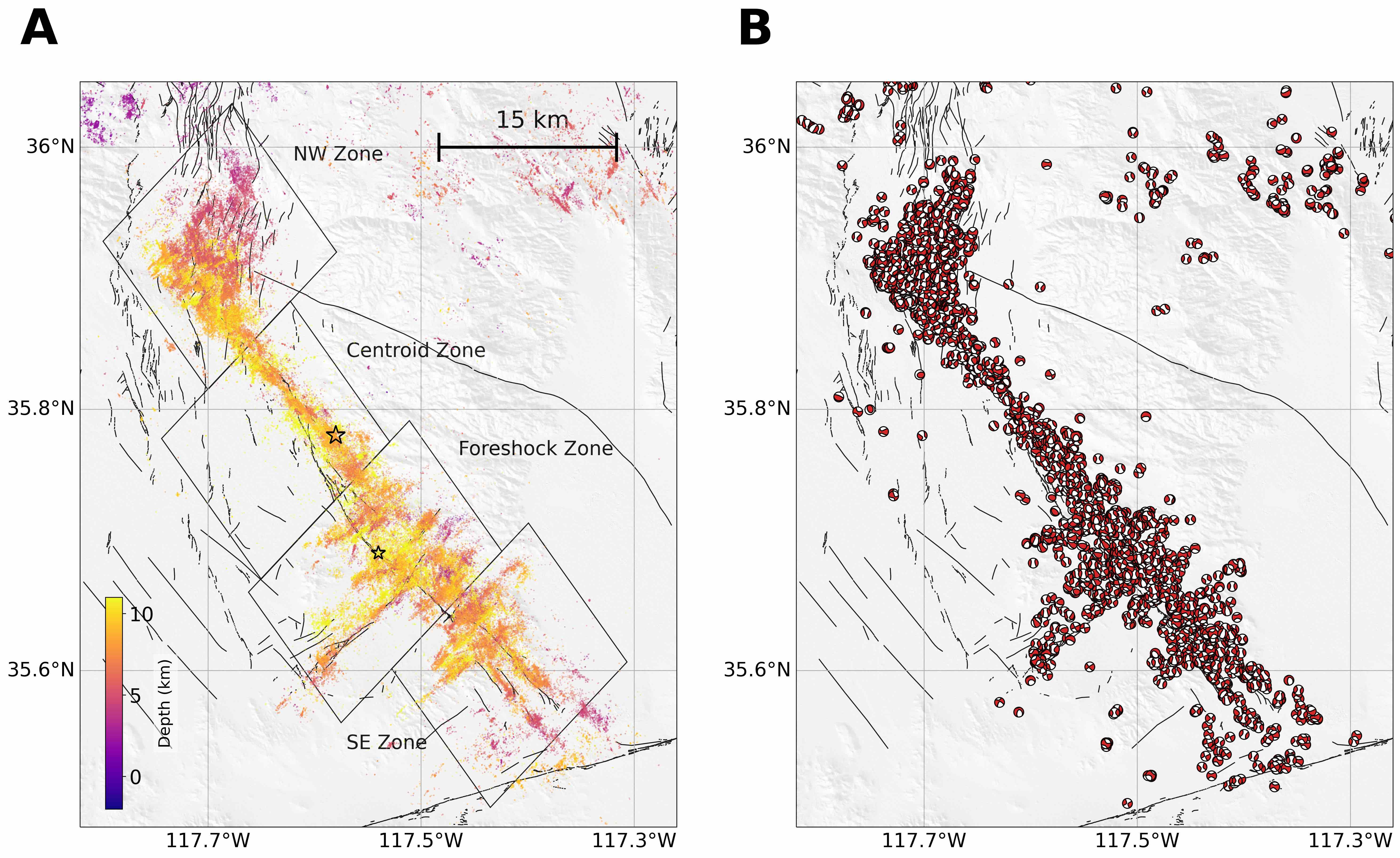

Stress Evolution Near a Big Earthquake (January 2025)

How the orientations of faults change throughout an earthquake sequence can tell us a lot about absolute stress in the crust and how stress is variably unloaded and reloaded in response to ruptures and postseismic deformation. In this study, we made a long-term seismicity and moment tensor catalog for the 2019 Ridgecrest sequence to look at how fault orientations change in response to the foreshock, mainshock, and postseismic deformation. Typically, focal mechanisms are used to measure changes in stress orientation throughout a sequence; however, we use a new technique from point process theory that uses seismicity to measure how fault orientations change throughout the sequence. Our results suggest a complex relationship between postseismic deformation and reloading. This new method also resolves a lower background differential stress than what is resolved from more standard focal mechanism-based techniques. Check out the paper here.

|

|---|

| Seismicity and moment tensor catalogs made in the study. |

Sharp Moho Variability Illuminated with Fiber Seismology (November 2024)

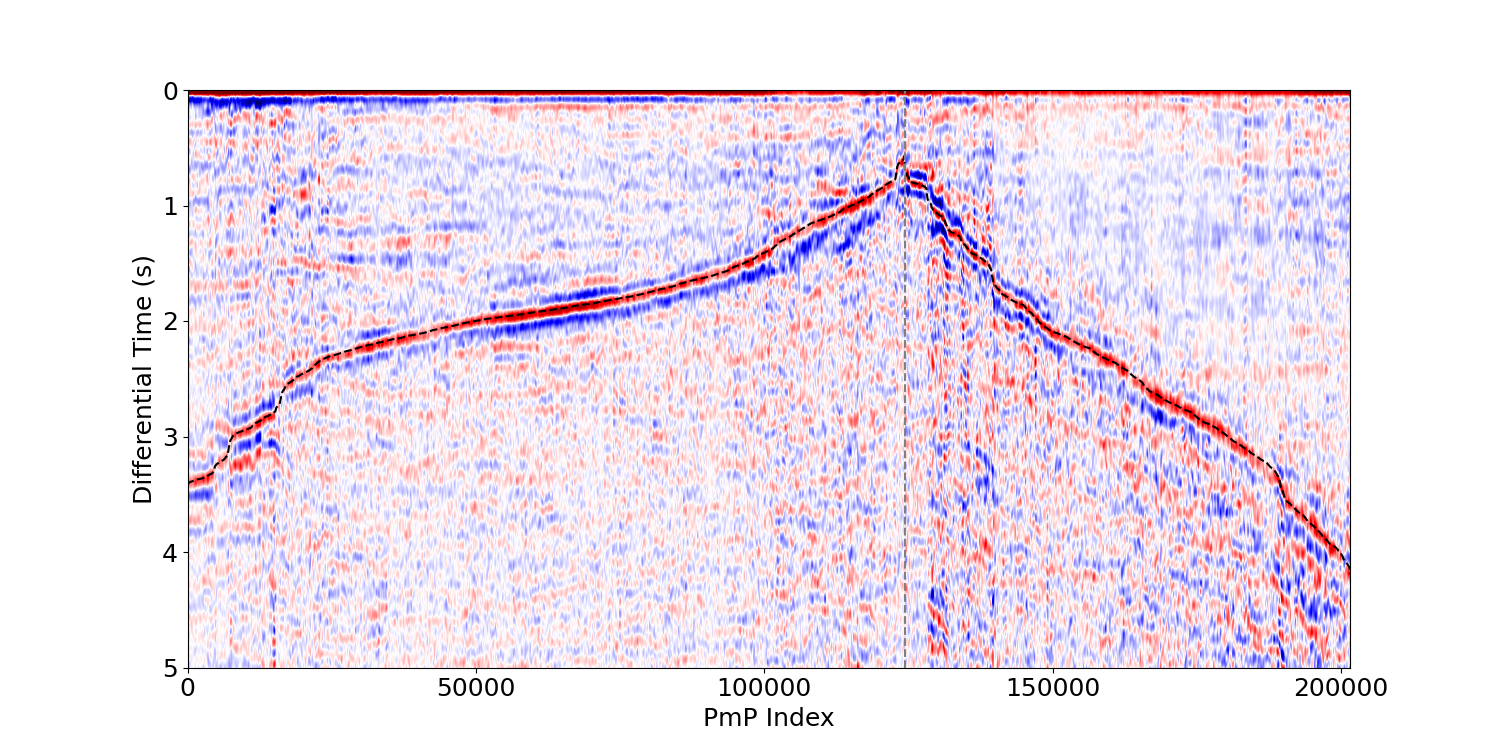

The topography of the Moho (crust-mantle boundary) can yield fundamental insights into tectonic evolution and the strength of the lithosphere. The Moho reflected phase (PmP) samples this key boundary and may be used in concert with the first arriving P phase to infer crustal thickness. The densely sampled station coverage of distributed acoustic sensing arrays allows for the observation of PmP at fine-scale intervals over many kilometers with individual events. We use PmP recorded by a 100-km-long fiber that traverses a path between Ridgecrest, CA and Barstow, CA to explore Moho variability in Southern California. With hundreds of well-recorded events, we verify that PmP is observable and develop a technique to identify and pick P-PmP differential times with high confidence. We use these observations to constrain Moho depth throughout Southern California, and we find that short-wavelength variability in crustal thickness is abundant, with sharp changes across the Garlock Fault and Coso Volcanic Field. Check out the paper in Science Advances here.

|

|---|

| Summary of the many PmP measurements made with our new technique. |

Estimating Stress Near a Megathrust Fault (November 2024)

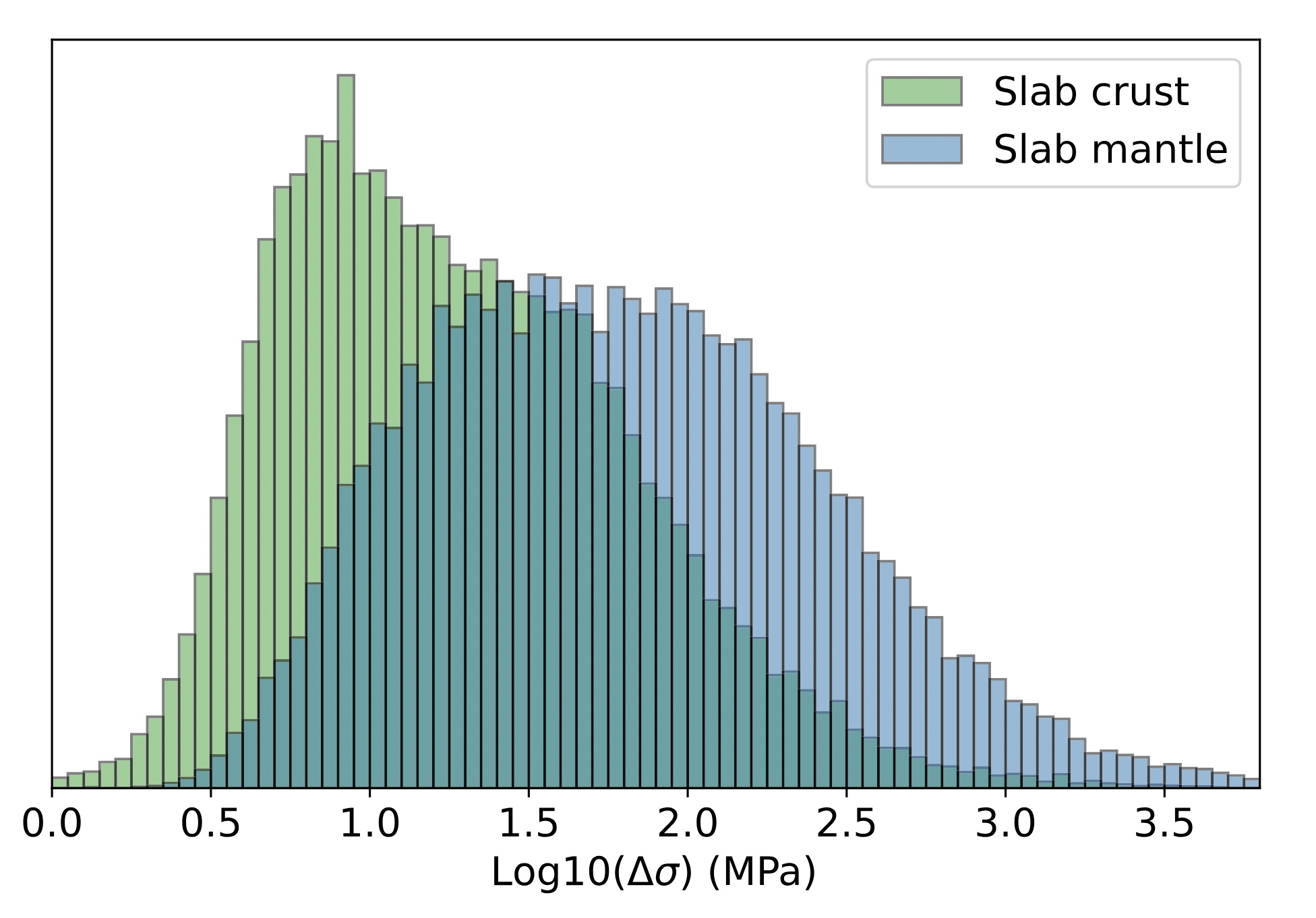

The stress level near a megathrust fault is important but hard to constrain. On 20 December 2022, a magnitude 6.4 strike-slip earthquake ruptured the Gorda slab in southern Cascadia. Led by Hao Guo, we relocate the aftershocks and later earthquakes using a high-resolution 3D velocity model and estimate rupture dimension and stress drop for several magnitude 4–5 aftershocks and recent earthquakes using the second moment method. Our stress-drop estimates are generally lower for earthquakes located in the slab crust compared to those a few kilometers deeper in the slab mantle. Combined, our results support a relatively low effective stress level near the megathrust in southern Cascadia, potentially due to elevated fluid pressures in the slab crust. Consequently, the ground motion in the onshore region above this low-stress section of southern Cascadia may not be as intense as that observed during great earthquakes in other subduction zones. Find the paper here.

|

|---|

| Demonstration of lower stress drops for earthquakes in the slab crust. |

Describing the Garlock Fault Zone with a Fiber (July 2024)

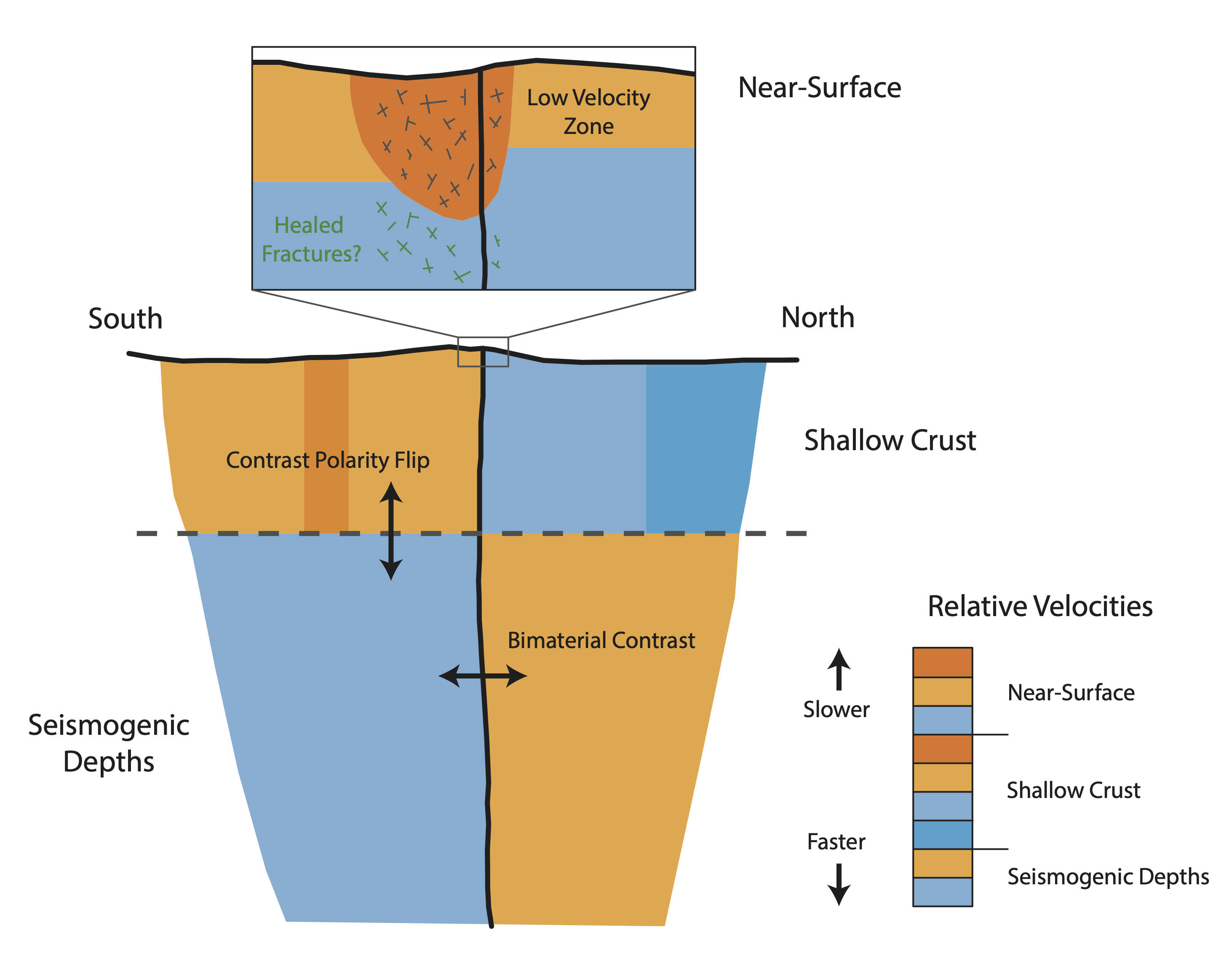

Earthquake ruptures happen within fault zones. The structure of fault zones and the physics of earthquakes are thus necessarily intertwined. The structure of fault zones at depth, where large earthquakes typically happen, is difficult to image because fault zones are narrow and seismic imaging resolution degrades with depth. Dense seismic arrays deployed across faults can help resolve important properties of fault zones at depth. Fiber optic seismology allows for the deployment of dense arrays across faults for long periods of time with low logistical burden. In our new study, we use a fiber-optic array that crosses the Garlock Fault, a major fault in Southern California, to explore important characteristics of the fault zone at different depths, and we notice several peculiar things. We find that there is no extensive low velocity feature at depth, which is unusual for a mature fault like the Garlock, potentially suggesting healing of the fault damage zone. Additionally, when we remove the contribution of the complicated velocity structure of the shallow crust, we recover a sharp velocity contrast across the fault which may have implications for the propagation behavior of future ruptures. Check out the study here.

|

|---|

| Schematic of the Garlock Fault Zone summarizing this study’s results. |

Finding patterns in strike-slip ruptures (November 2023)

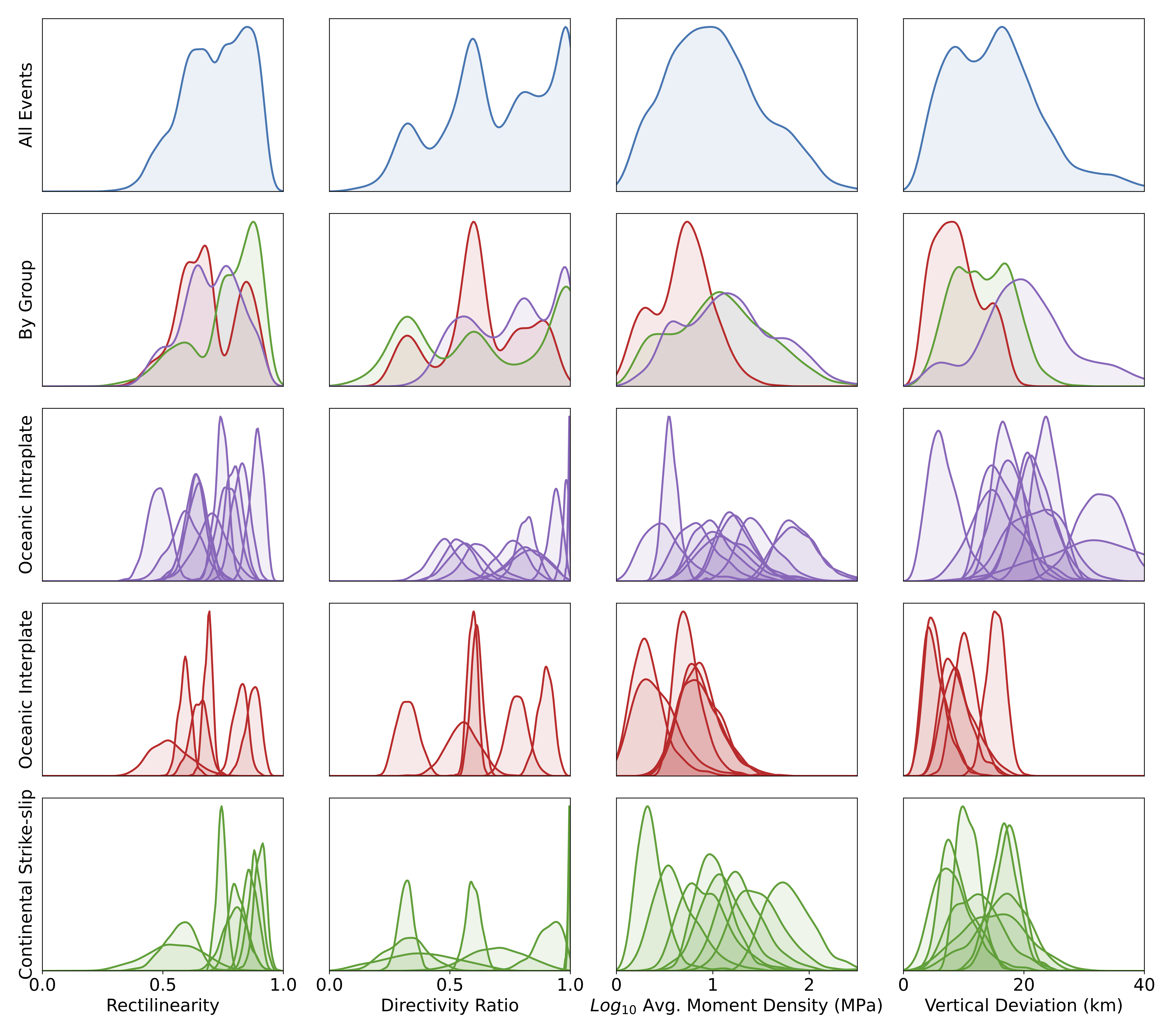

Earthquake ruptures are complicated processes, and their behavior depends on encompassing structure. Characterizing this dependence is valuable, but it is challenging because it requires the systematic evaluation of rupture properties for many events. In this work, we apply a low-dimensional, Bayesian rupture inversion framework to every large strike-slip earthquake of the past three decades. This technique allows us to obtain objective, probabilistic characterizations of all these sources, so that we can confidently identify patterns in rupture behavior with structure. We make several interesting observations, including observations about the directivity of ruptures, the rheology of faults that host large oceanic earthquakes, and the sources of weakness in the oceanic crust that allow for large ruptures in the interior of oceanic plates. Check out the paper here.

|

|---|

| Distributions of source quantities computed in this study organized by tectonic region. |

Finding and describing little faults (November 2022)

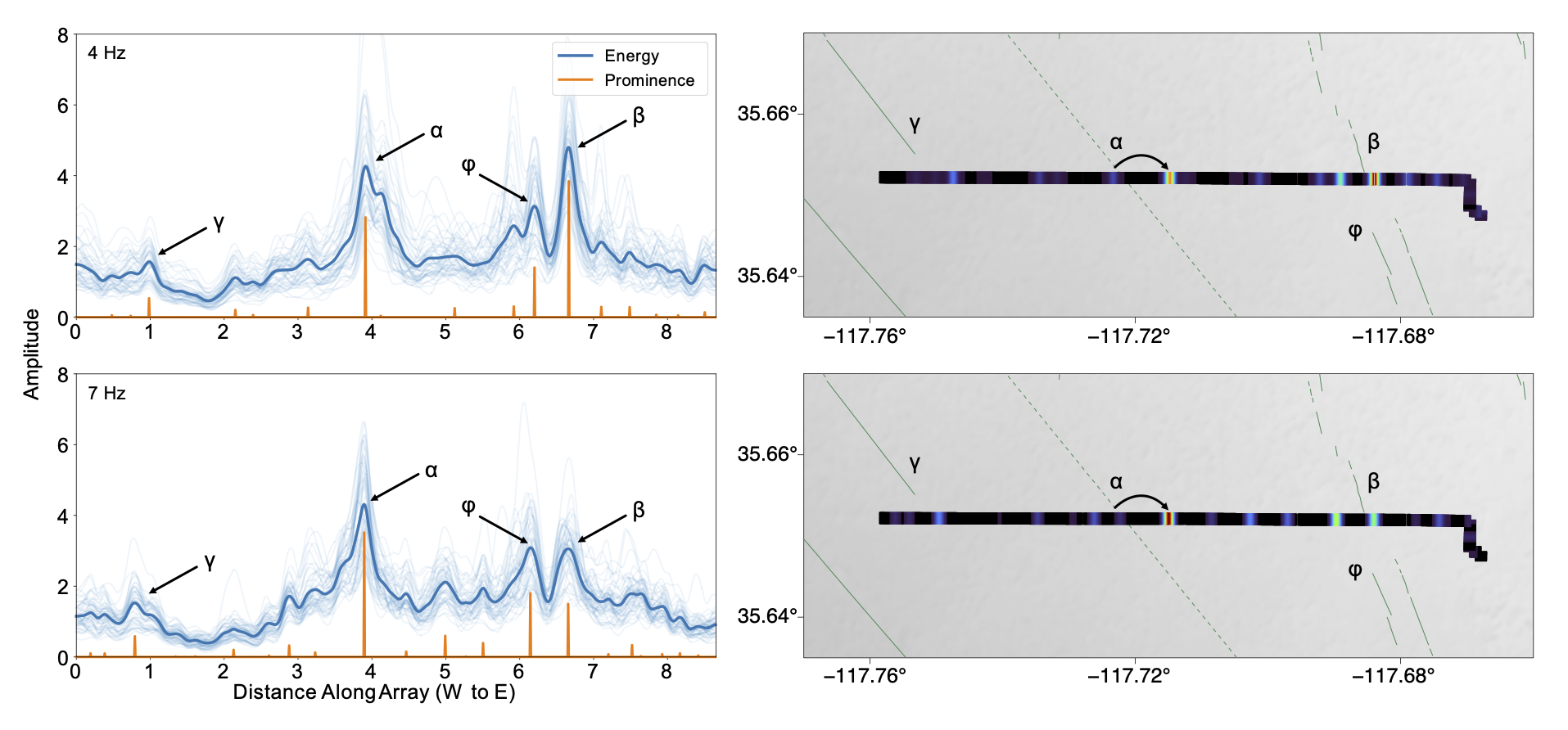

Fault zones are structures that control where and how earthquakes happen. These structures span many scales, and better characterizing faults across these scales contributes to our understanding of these important structures. Small-scale fault zones occupy an observational gap that has historically been challenging to bridge. We develop and implement an approach for finding and characterizing small-scale fault zones using locally scattered surface waves in the earthquake wavefield recorded by distributed acoustic sensing arrays. In this study, we project scattered surface waves backwards in time to locate their source, and we find that the locations of these scatterers are correlated with mapped fault locations. We then develop a fault model and perform synthetic tests to see what we can learn about these faults. We find that by comparing our synthetics with our data, we can constrain the dimensions of these small fault zones. Check out the full paper here. This paper pairs nicely with another paper that I helped with that uses scattered waves in the ambient noise wavefield. That paper can be found here.

|

|---|

| Amplitude of the backprojected scattered wavefield at different frequencies on the left and comparison of these amplitude profiles to mapped faults in the area on the right. |

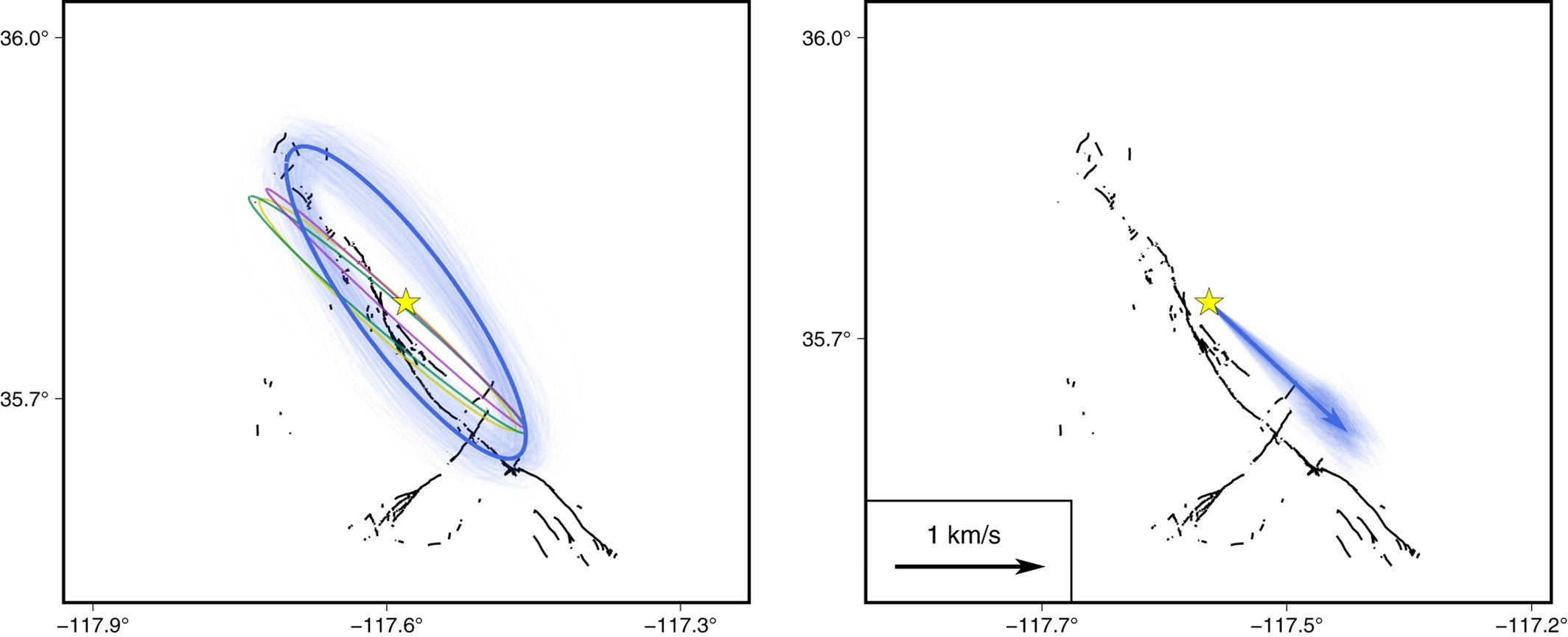

Robustly describing earthquake ruptures (Mar 2022)

Earthquake ruptures mostly happen deep within the Earth, and seismologists try to describe these ruptures using wiggles produced by seismometers that are usually far away and at the surface of the Earth. So, data coverage in seismology is inherently deficient, and this makes solving for rupture parameters challenging. Typically, seismologists try to infer rupture parameters using complicated optimization problems that are poorly constrained. To get more robust estimates of rupture parameters, we developed a framework to solve for so-called stress glut second moments using a fully Bayesian inverse scheme. In short, this framework can yield a low-dimensional, probabilistic description of an earthquake rupture’s spatial extent, propagation direction, and duration. We successfully test this technique on the 2019 Mw 7.1 Ridgecrest Earthquake. Check out the article here.

|

|---|

| Representation of the second moments of the stress glut for the 2019 Mw 7.1 Ridgecrest Earthquake. |

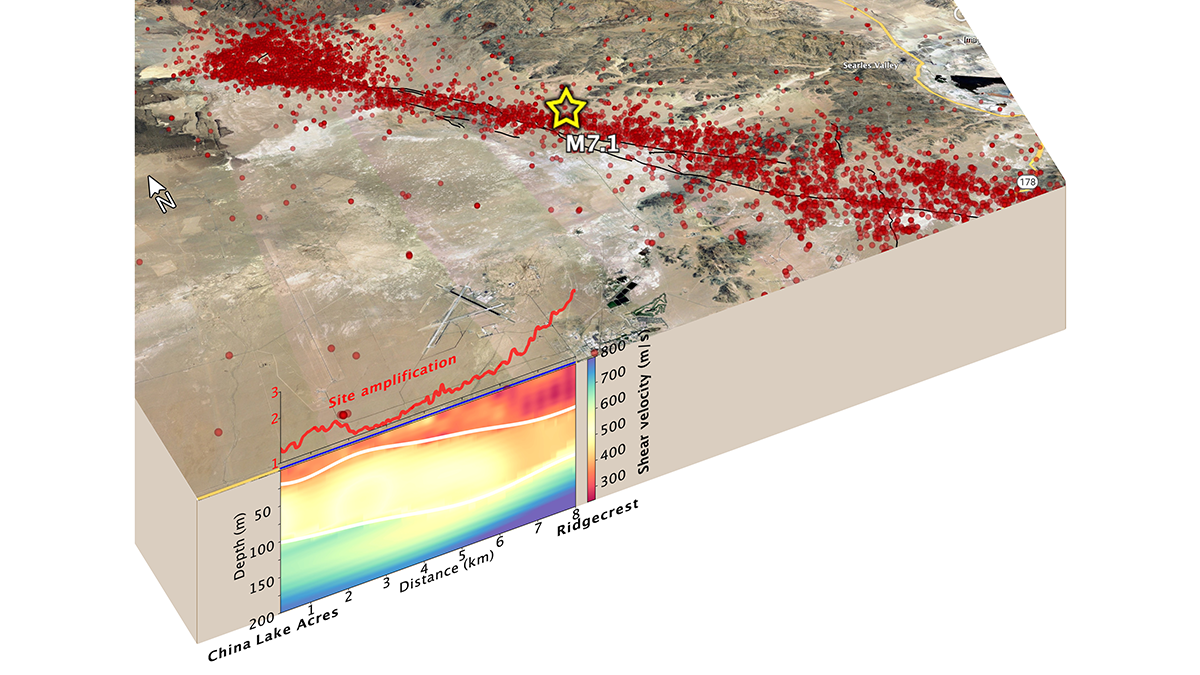

Exploring ground shaking variability (Dec 2021)

Earthquake hazards estimation is complicated and requires the consideration of numerous important variables. One such important variable is local geology. For example, sedimentary basins like the Los Angeles Basin, which hosts most of the city’s population, are known to amplify ground motion. These geologic structures occur at many scales, including the scale of city blocks. For this reason, identical houses just a few blocks apart could experience highly variant damage from the same earthquake. In this work led by my fellow graduate student, Yan Yang, we leverage the high spatial sampling of distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) to image shallow Earth structure at high resolution near Ridgecrest, CA. We show that the subsurface varies significantly over the distance of a few kilometers. We also find that this structural variability is highly correlated with ground motion variability observed from earthquakes recorded near the array. Check out the EOS feature of this work here. Check out the manuscript here.

|

|---|

| Summary image showing the velocity model and ground motion variability in the context of the 2021 Ridgecrest Earthquake sequence (from EOS article) |

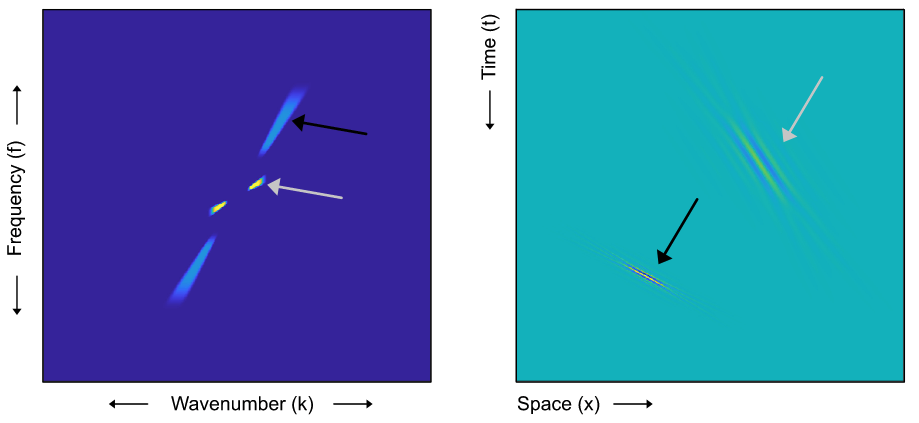

Illuminating blurry signals (Oct 2021)

Distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) is an emergent technology that converts fiber optic cables into dense arrays of strainmeters. This technology may prove transformational because it makes deploying dense seismic arrays relatively easy. But the sensitivity of DAS as a measurement tool is limited by both random noise (instrumental deficiencies) and nonrandom noise (nearby traffic and construction). In pursuit of a technique to remove these sources of noise, we look to curvelets, functions that are very good at representing images with curved boundaries. Using curvelets, we define a framework through which we can partition the DAS-measured wavefield so that we may isolate our desired signal from noise. We show that this technique works by illuminating many Southern California earthquakes that were previously masked by noise. Check out the manuscript here.

|

|---|

| Examples of curvelets (affectionately called “little plane waves”) in the frequency-wavenumber and spatiotemporal domains. |

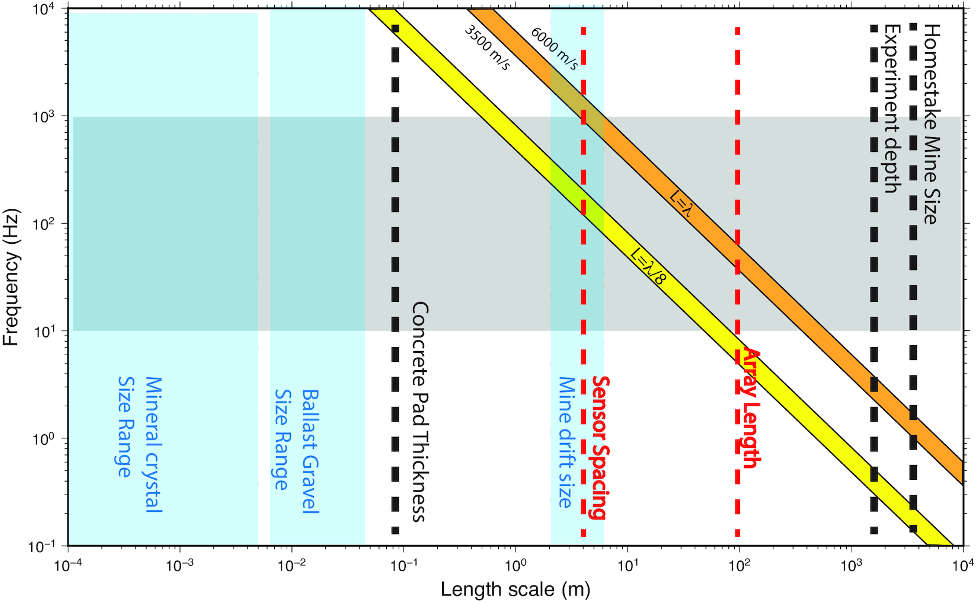

Sensing the fabric of rocks (Jan 2021)

Many metamorphic rocks have a so-called “fabric.” This fabric exists because these rocks are smushed so much during metamorphism, the crystals in the rocks become systematically aligned. This alignment makes these rocks anisotropic, meaning their elastic properties change with orientation. Although we expect anisotropy in rocks to affect our seismic observations at all scales, there have been few studies that examine how anisotropy might affect seismic observations at scales in between those of hand-samples and large crustal models. In our recent study, which includes the bulk of my undergraduate thesis, we set out to better understand anisotropy at these intermediate scales. To do this, we examined directional variability in P-wave travel-times and particle-motions using high frequency data from an active source experiment performed in the Homestake Mine in South Dakota. Check out the full paper here.

|

|---|

| Illustration of the scales of heterogeneities that may influence the anisotropy measurements in this study. |